Wednesday, December 3, 2025

Tuesday, December 2, 2025

Real Clear Politics is part of the problem, not the solution

Friday, November 14, 2025

It's very amusing that Kevin Sorbo thinks MAGA voters will refuse to vote Republican in the midterms because Trump said we don't have enough talent in this country

Why people vote is emotional to these people, not rational.

"I'm insulted Trump thinks Americans have no talent so I'm voting for the other guy".

OK whatever.

Trump meanwhile pretended in the interview with Laura Ingraham that he had nothing to do with the round-up and deportation of hundreds of Koreans from the Georgia battery plant, which was basically Obama's MO throughout his presidency when a problem occurred in the country under his watch.

"You didn't build that over there, and I didn't do that other thing over here."

... The Georgia facility, operated by Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution, saw 475 of its workers arrested on allegations that they were in the U.S. illegally, or without the proper work permits, with hundreds of detained South Koreans sent home Thursday.

The raid was part of a broader deportation drive by the Trump administration, which the White House has described as central to fulfilling U.S. President Donald Trump’s election campaign promises. Stephen Miller, the White House’s deputy chief of staff and homeland security adviser, has pushed for 3,000 arrests a day. ...

Tuesday, November 4, 2025

Friday, October 31, 2025

Irony alert: Masked ICE, DHS, CBP employees who get to hide their identities roam the streets with facial recognition capability to gather images and fingerprints of citizens

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

You thought you were voting for deportations of illegals, and you got an Obama-style police state instead.

If you see ICE, CBP, DHS on the street, turn around and go the other way, and vote against these bastards.

You Can't Refuse To Be Scanned by ICE's Facial Recognition App, DHS Document Says

... On Wednesday 404 Media reported that both ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are scanning peoples’ faces in the streets to verify citizenship.

... The app can also scan peoples’ fingerprints and provide information based on those, and uploads location data “so ICE can identify where the encounter took place.”

“Although the intended purpose of the Mobile Fortify Application is to identify aliens who are removable from the United States, users may use Mobile Fortify to collect information in identifiable form about individuals regardless of citizenship or immigration status. It is conceivable that a photo taken by an agent using the Mobile Fortify mobile application could be that of someone other than an alien, including U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents,” the document continues.

... “By using the Mobile Fortify app to provide real-time responses to biometric queries, ICE officers and agents can reduce the time and effort to identify targets compared to existing manual processes,” the document says.

Tuesday, October 21, 2025

These two pixies John J. Waters and Adam Ellwanger can't point to one thing which Democrats have achieved which Donald Trump has permanently reversed or topped

... By the time Obama secured his second term as president, the Democratic party (and the shadow groups that swim in its wake) had won the day on virtually every issue that mattered. This victory was largely due to their focus on doing and creating things rather than thinking about them. ...

Democrats owned the world of things and the real-world effects of their policies – however incoherent – were evident to all. An underlying premise of the Trump campaign was a return to things. To infrastructure. To clean streets and safe cities. To American-made products. And to historic landmarks and monuments that memorialize America’s greatness for future generations. Trump recognized that conservative ideas are meaningless until we rebuild the material conditions where they can be achieved. ...

More.

There isn't one thing in the room with us right now, and there won't be.

We are three weeks into a government shutdown and Congressional Republicans are completely OK with these precious legislative days just thrown into the dumpster of history without accomplishing anything.

The US House isn't even in session, and hasn't been in session now but for 3 of the last 16 weeks, and this will likely extend to 17, 18, who knows how many weeks. Some people are predicting to Thanksgiving.

The GOP won't swear in Democrat Adelita Grijalva, elected on September 23rd, because they fear Republican Thomas Massie's Epstein gambit.

Donald Trump's GOP is a farce.

Saturday, October 18, 2025

Wednesday, October 8, 2025

Year to date spot gold is up ~54%

By comparison, Total Stock Market Index VTSAX is up 14.83% ytd through yesterday.

Total Bond Market Index VBTLX is up 6.4%.

... The [gold] rally has been driven by a cocktail of factors, including . . . a weak dollar. ... -- CNBC

Would these people know a weak dollar if they saw it?

Trying to explain gold like this is just silly.

The Nominal Broad U.S. Dollar Index is 120.51, down 7.4% from the January all time high of 130.21.

The all time low for this index was under Obama in July 2011, at 85.46.

You remember the summer of 2011, right?

The dollar was at its weakest, America lost its AAA rating, and precisely net zero jobs were created that August, the first time since WWII.

We have a strong dollar today, not a weak one.

Wednesday, October 1, 2025

How the U.S. Army got woke under Obama

This was published just over ten years ago. It's still up there, for all the world to see.

Female Rangers Were Given Special Treatment, Sources Say

Women were given special treatment before and during Ranger School to ensure at least one would graduate, sources say.

By Susan Katz Keating, a stringer at PEOPLE. She has written about major crime, along with military topics, for more than two decades.Way back in January, long before the first women attended the Army’s elite Ranger School – one of the most grueling military courses in the world – officials at the highest levels of the Army had already decided failure was not an option, sources tell PEOPLE.

“A woman will graduate Ranger School,” a general told shocked subordinates this year while preparing for the first females to attend a “gender integrated assessment” of the grueling combat leadership course starting April 20, sources tell PEOPLE. “At least one will get through.”

That directive set the tone for what was to follow, sources say.

“It had a ripple effect” at Fort Benning, where Ranger School is based, says a source with knowledge of events at the sprawling Georgia Army post. “Even though this was supposed to be just an assessment, everyone knew. The results were planned in advance.”

On Tuesday, PEOPLE revealed that Oklahoma Republican Rep. Steve Russell had asked the Department of Defense for documents about the women who attended Ranger School after becoming concerned that “the women got special treatment and played by different rules,” sources say.

Ranger School consists of three phases: Benning, which lasts 21 days and includes water survival, land navigation, a 12-mile march, patrols, and an obstacle course; Mountain Phase, which lasts 20 days, and includes assaults, ambushes, mountaineering and patrols; and Swamp Phase, which lasts 17 days and covers waterborne operations.

But whereas men consistently were held to the strict standards outlined in the Ranger School’s Standing Operating Procedures handbook sources say, the women were allowed lighter duties and exceptions to policy.

Multiple sources told PEOPLE:

• Women were first sent to a special two-week training in January to get them ready for the school, which didn’t start until April 20. Once there they were allowed to repeat the program until they passed – while men were held to a strict pass/fail standard.

• Afterward they spent months in a special platoon at Fort Benning getting, among other things, nutritional counseling and full-time training with a Ranger.

• While in the special platoon they were taken out to the land navigation course – a very tough part of the course that is timed – on a regular basis. The men had to see it for the first time when they went to the school.

• Once in the school they were allowed to repeat key parts – like patrols – while special consideration was not given to the men.

• A two-star general made personal appearances to cheer them along during one of the most challenging parts of the school, multiple sources tell PEOPLE.

The end result? Two women – First Lts. Kristen Griest and Shaye Haver – graduated August 21 (along with 381 men) and are wearing the prestigious Ranger Tab. Griest was surprised they made it.

“I thought we were going to be dropped after we failed Darby [part of Benning] the second time,” Griest said at a press conference before graduation. “We were offered a Day One Recycle.”

At their graduation, Maj Gen. Scott Miller, who oversees Ranger School, denied the Army eased its standards or was pressured to ensure at least one woman graduated.

“Standards remain the same, Miller said, according to The Army Times. “The five-mile run is still five miles. The 12-mile march is still 12 miles.

“There was no pressure from anyone above me to change standards,” said Miller, who declined to speak to PEOPLE.

Instructors say otherwise.

“We were under huge pressure to comply,” one Ranger instructor says. “It was very much politicized.”

The women didn’t want or ask for special treatment, says one who attempted the program.

“All of us wanted the same standards for males and females,” Billi Blaschke, who badly injured her ankle only six days into a required pre-assessment program, tells PEOPLE. “We wanted to do it on our own.”

On September 2, the Army announced that Ranger School is now open both to men and women.

Women are not currently allowed to perform Ranger duties, even Lts. Griest and Haver who passed the course. However, the Army will be forced to open Ranger positions to females on January 1, unless the Secretary of Defense grants an exception.

If the exemption isn’t granted, the Army may send women into combat – which is why so many former and current Rangers are concerned about women being held to the same standards as men.

“Combat is brutal and unforgiving,” says Jim Lechner, a retired Army officer and Ranger who was wounded in combat in Mogadishu, Somalia, during the famed “Black Hawk Down” incident. “Fighters must be prepared and capable. If they are not, people will die.”

Ranger School teaches students how to overcome fatigue, hunger and stress to lead soldiers in small-unit combat operations.

“I remain unconvinced that the recent graduation of two female soldiers was a proper test of females’ ability to perform in combat,” Lechner tells PEOPLE.

While Griest and Haver could not be reached for comment, the Army insists the two women who graduated August 21 did so under their own steam.

“In order to successfully graduate Ranger School, all students, male and female, are required to meet all course standards,” Army spokesman LTC Jennifer Johnson tells PEOPLE.

“The course standards for Ranger Class 08-15 are the exact same standards that have been used for all other Ranger classes,” she says.

Claims of Special Treatment

The women got special treatment from the start, sources tell PEOPLE.

Though the course didn’t begin until April 20, the first female Ranger candidates arrived at Fort Benning in January to attend the National Guard’s rigorous Ranger Training and Assessment Course (RTAC), a two-week program designed to assess whether a student could attempt the 62-day Ranger School.

Previously, only the National Guard’s Ranger hopefuls were required to attend RTAC, while non-Guard candidates had the elective option to attend. Now, all females – no matter whether they were Guard, Reserve or Regular Army – were required to attend.

There they were given another edge, sources say: While men were held to a stark pass-fail standard, women were allowed to redo the special training repeatedly.

“That was the first special concession,” says an Army source with knowledge of what transpired. “Males do not recycle RTAC. They either cut it or not.”

Neither Gen. Miller nor Fort Benning responded to questions asking about allegations of altered standards.

Approximately 140 women went through various cycles of the 14-day long RTAC. Many left of their own volition. Others dropped out, sources say.

By the end of January, many were slated to begin Ranger school.

Then came the second round of special treatment, sources tell PEOPLE.

The males proceeded to Ranger School without further ado. The women got special training. They were placed into their own platoon and spent the next several weeks preparing for Ranger School, sources say.

They were given nutritional counseling and a soldier to train them full time. The soldier, Sergeant First Class Robert Hoffnagle, previously had competed in Fort Benning’s annual Best Ranger competition, touted as the “ultimate test of fitness, endurance and grit for the Army’s most elite soldiers.

The women “lived and breathed nothing but Ranger School 24/7,” a source tells PEOPLE. “He taught [them] everything, including how to do patrols.”

There they were also allowed to train and rehearse on Land Navigation.

“That right there was a special consideration that only was given to the women,” says a source with knowledge of events. “It’s not fair, on a lot of levels.”

In a response to questions that included a request for confirmation that the women were placed in the special platoon, Army spokesman Lt. Col. Ben Garrett said “the allegations are not true.”

However, other sources confirmed its existence to PEOPLE.

“Hoffnagle got us ready for Ranger School,” says a woman who attended the special platoon.

And other sources at Fort Benning tell PEOPLE they were present at meetings to discuss the platoon’s budget and how it would operate.

By April 20, 19 women and 381 men reported for Ranger School.

Within days, 11 women were dropped from the course because they failed either the physical training, land navigation, or road march portions, sources say.

“They were decimated on road march,” an instructor tells PEOPLE.

On May 7, less than three weeks into the course, a highly placed Army source told PEOPLE that no women remained in Ranger School.

Then something changed.

“The women were called in to see the general,” said the source, referencing Miller, who oversees Ranger School.

“He told them they could not quit – too much time and money had been devoted to bringing them here,” the source said.

Miller himself acknowledged he’d met with the women in a statement to The Washington Post, though he did not say what he told them, just that he was “impressed” that they wanted to continue, according to the newspaper.

On May 8, eight women were allowed to repeat the first phase.

Once again, the women failed, sources said. They stumbled on patrols.

“They were not aggressive enough,” a source with knowledge of events tells PEOPLE. “They made poor combat decisions.”

Patrols are a crucial element in Ranger School.

“If you fail patrols, it’s significant, because you don’t have what it takes,” says Bubba Moore, a former Ranger Instructor with close ties to the Ranger and Fort Benning communities. “People will get killed.”

In late May, with more failed events, commanders reassessed what to do with the women. Five women were sent back to their home units. Three were offered the chance to start Ranger School all over again, from the first day. They accepted the offer.

The three women again failed patrols during the first phase, sources say.

That’s when Gen. Miller himself arrived on the course, according to sources.

Fort Benning later acknowledged to PEOPLE that Miller had gone to the training grounds while the women were on the course. A Fort Benning spokesman said Miller went there to commemorate his 30th anniversary of attending Ranger School, and did not go to pressure instructors into passing the women.

Nevertheless, with Miller on scene, the women passed and progressed to the next phase.

“Was it undue command influence?” a source with knowledge of events tells PEOPLE. “No matter what the general intended to convey, the instructors had no choice but to take this to mean, ‘Play along.’ ”

“The instructors knew what they were expected to do,” the source says. “They did it.”

After the women continue to struggle, Miller showed up again, sources say. Two women passed and ultimately graduated on August 21.

Meanwhile, one woman from that same class, who has redone other phases repeatedly, just failed the Swamp Phase and is going to try it again, sources say.

Another group of women is set to begin Ranger School in November.

Late on the evening of Sept. 25, the Army released a statement from Brig. Gen. Malcom B. Frost, who is chief of the Army’s public affairs office, about the PEOPLE story and the allegations uncovered by PEOPLE reporter Susan Keating.

[Ms. Keating] claimed that women were allowed to repeat a Ranger training class until they passed, while men were held to a strict pass/fail standard,” the statement said. “That is false.

“She charged that women regularly practiced on Ranger School’s land navigation course while men saw it for the first time when they went to the school,” the statement said. “Again, false.

“She accused an Army general of calling female candidates together to tell them they could not quit the course. Yet again, false.

https://people.com/celebrity/female-rangers-were-given-special-treatment-sources-say/

Friday, September 19, 2025

I keep hearing that gold is soaring because of continued dollar weakness lol

On the contrary, gold has risen despite continued dollar strength.

The enormous gains for gold in 2024 and 2025 are not explained by a round trip in the dollar index from 120 to 129 and back again. That's just a little side show in the bigger picture of dollar strength.

The dollar index has made steady progress out of the pit of despair at 85.46 in July 2011 under Barack Obama, the enemy of fossil fuels, to a place of relative strength today averaging above 120 in 2022 and 2023, 123 in 2024, and 125 in the first half of 2025.

Speaking of a weak dollar in this context is laughable.

Maybe the dollar is so strong again because the United States has become a net exporter of oil. The 1975 ban on oil exports was lifted in December 2015. Net imports of oil went negative for the first time since 1950 in 2020.

Gold is probably so strong in part because of increasing debt globally, which like rising prosperity helps drive demand for it as a hedge. Extreme poverty gripped half the world in 1950 but by 2020 it afflicts just 10%. Meanwhile gold production has nearly tripled over the period.

As a percentage of global GDP, global debt has gone from just above 100% of global GDP in 1980 to a whopping 235% of global GDP in 2024.

Thursday, September 18, 2025

Trump is The Decider Bush 43, Obama, and Biden wrapped into one: junking due process, designating people terrorists without evidence and ignoring the evidence when they are, censoring speech, and generally making a mockery of the rule of law

Friday, August 29, 2025

Friday, August 1, 2025

Mad King Ludwig fires BLS commissioner in a fit of rage over his bad jobs numbers, blaming the messenger

Banana republic stuff from the Banana Republican.

Trump is unfit to be president.

Trump fires commissioner of labor statistics after weaker-than-expected jobs figures slam markets

William Beach, a 2017 Trump appointee and McEntarfer’s immediate predecessor at BLS, also sharply criticized her firing.

“The totally groundless firing of Dr. Erika McEntarfer, my successor as Commissioner of Labor Statistics at BLS, sets a dangerous precedent and undermines the statistical mission of the Bureau,” Beach posted on X.

“This escalates the President’s unprecedented attacks on the independence and integrity of the federal statistical system,” Beach added in a statement. “The President seeks to blame someone for unwelcome economic news.” ...

Friday, July 25, 2025

Wednesday, July 23, 2025

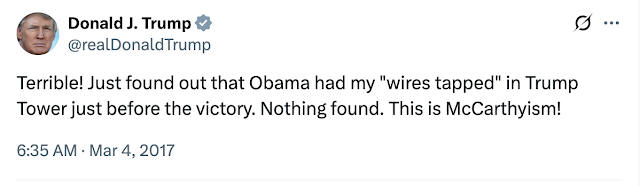

Like shooting fish in a barrel, except Obama really did wiretap Trump in 2016-2017: The left attacks Trump for saying Epstein is old news and focus on old Obama news instead

That's how they got Manafort after all.

As ever, it is primarily Trump's own clumsy mouth which is what gets him into trouble and keeps him from respectability, but that doesn't mean he isn't right about Obama.

Tuesday, July 15, 2025

Different parties, same federal incompetence: Obama's EPA polluted the Animas and San Juan Rivers with 3 million gallons of toxic mine waste, 10 years later Trump's National Park Service burns down the Grand Canyon

Monday, July 14, 2025

Saturday, June 28, 2025

Trump is the Uniparty, floats an Iran policy similar to Obama's

Saturday, June 21, 2025

The U.S. Senate parliamentarian still has not ruled on the GOP's wacky current policy vs. current law baseline

The current policy is the temporary Trump tax cuts from 2017.

The current law is the tax compromise worked out by Barack Obama and John Boehner.

I don't think this thing is going to be done by the Fourth of July.

GOP’s food stamp plan is found to violate Senate rules. It’s the latest setback for Trump’s big bill

... The parliamentarian’s office is tasked with scrutinizing the bill to ensure it complies with the so-called Byrd Rule, which is named after the late Sen. Robert C. Byrd, D-W.Va., and bars many policy matters in the budget reconciliation process now being used. ...

Some of the most critical rulings from parliamentarians are still to come. One will assess the GOP’s approach that relies on “current policy” rather than “current law” as the baseline for determining whether the bill will add to the nation’s deficits. ...

The truth is buried in the very last paragraph: Obama's war on coal did this to us

... certain facilities like old fossil-fuel powered plants have been decommissioned and new energy capacity to replace it has been relatively slow to come online ...